What is issue management (definition)?

Issue management is the ugly duckling of crisis communication – not much attention is paid to it in corporate communication. However issue management is a central concept in our profession.

Definition of issue management: an issue is a topic that is important for your organization, and around which stakeholders “organize”.

An issue is a topic around which stakeholders “organize”

That is to say, that stakeholders take deliberate actions to make their position clear with respect to your issue or organization. Sometimes, these are external stakeholders (like environmental organizations), but they can also be internal (like trade unions). Stakeholders can take the same line as the organization, but issue management is, of course,especially about the stakeholders who are not (entirely) aligned with the organization.

If things really get out of hand with that difference of opinion, an issue can end in a crisis. In a crisis, stakeholders take a stance that is opposite to your organization – and succeed in winning more and more previously neutral or uninterested stakeholders to their side. For example: the media, and via them the general public.

According to some authors, the entire discipline of corporate communication can be defined as following up on and managing (potential, new and existing) issues and stakeholders.

What is the difference between issuemanagement and crisis communication?

Many articles have been written about the differences and likenesses of issues and crises.

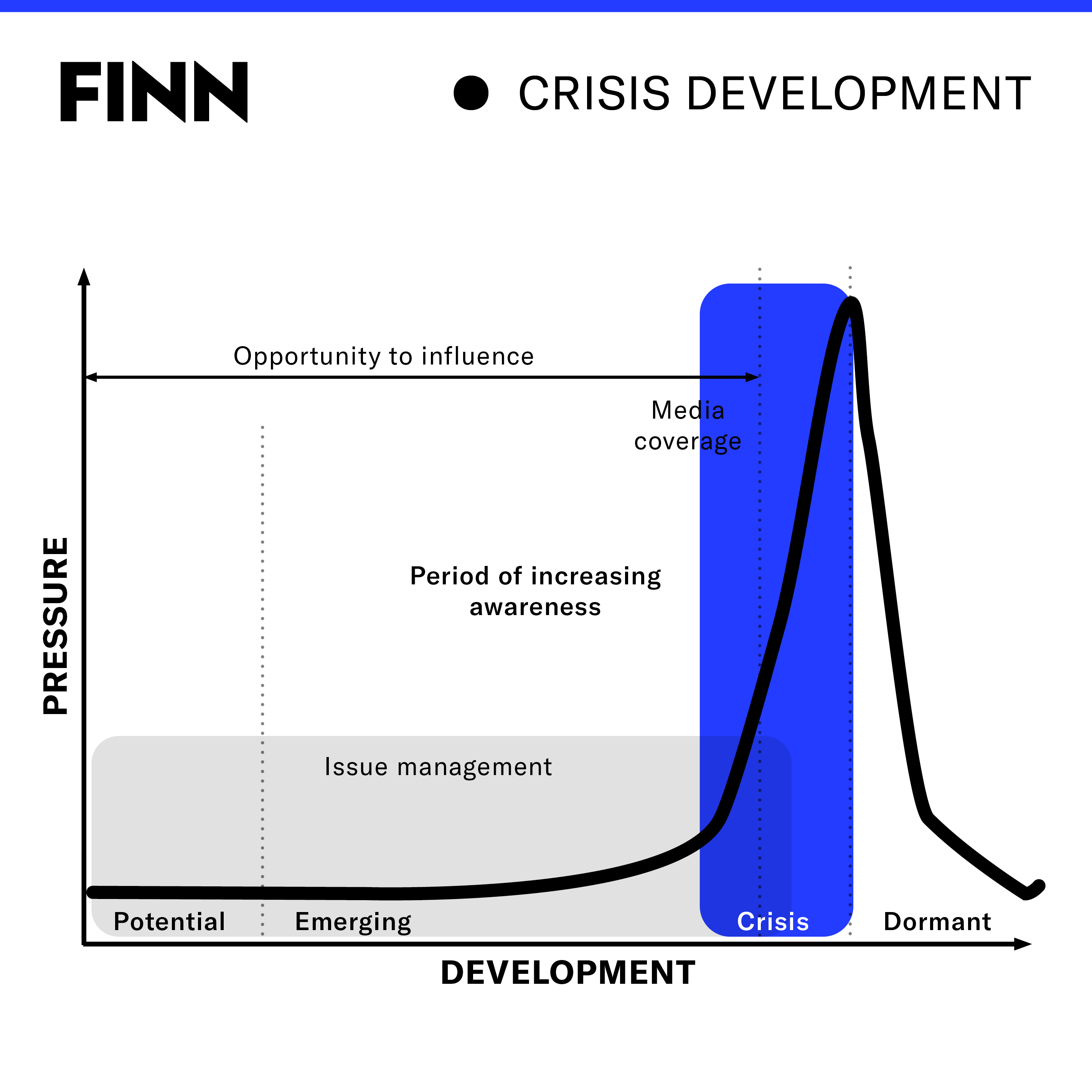

Let’s assume that issues are not crises, but could become one. The accompanying diagram is frequently used: an issue becomes a “real” crisis when it gains momentum in the media and in public opinion:

However, that tipping point when an issue becomes a crisis is not always easy to determine.

You do not end up in a crisis because a (negative) article appears on an issue.

Why is the difference issue – crisis important?

The distinction between an issue and a crisis is very important to how you tackle your response.

A crisis rarely blows over. Not reacting during a reputational crisis – or leaving the initiative to other stakeholders in a crisis is often a bad idea. If a crisis really erupts, the damage can be considerable.

But an issue that emerges briefly can also disappear into the background without causing much or permanent reputational damage. Sometimes activist groups do their level best to put a topic on the table (and keep it there), but the media do not take it up, or only sporadically and not in a concerted manner. In such a case, reacting to the issue can actually breathe life into it and result in an actual crisis.

What do you have pay attention to if you have to deal with an issue?

The moment an issue comes to the surface, it is therefore vital to evaluate whether it will die a natural death, or whether it will gain momentum and perhaps turn out to be much more than a storm in a teacup.

The question is: How can you know whether you find yourself on the tipping point between an issue and a real crisis – or whether you are witnessing a temporary blip?

One solution consists of convening a meeting within your organization and seeking everyone’s opinion. This is a frequently used technique, but is not without risk.

The risk exists in both directions: we sometimes have to restrain customers from taking legal action against stakeholders who have no or hardly any impact on the debate (overreaction). That overreaction carries the risk of creating a conflict that will draw media interest.

On the other hand, we sometimes have to persuade CEOs that a head-in-the-sand strategy is not the correct response to (impending signs of) a real crisis. It is therefore better to map out issues properly with a good tool.

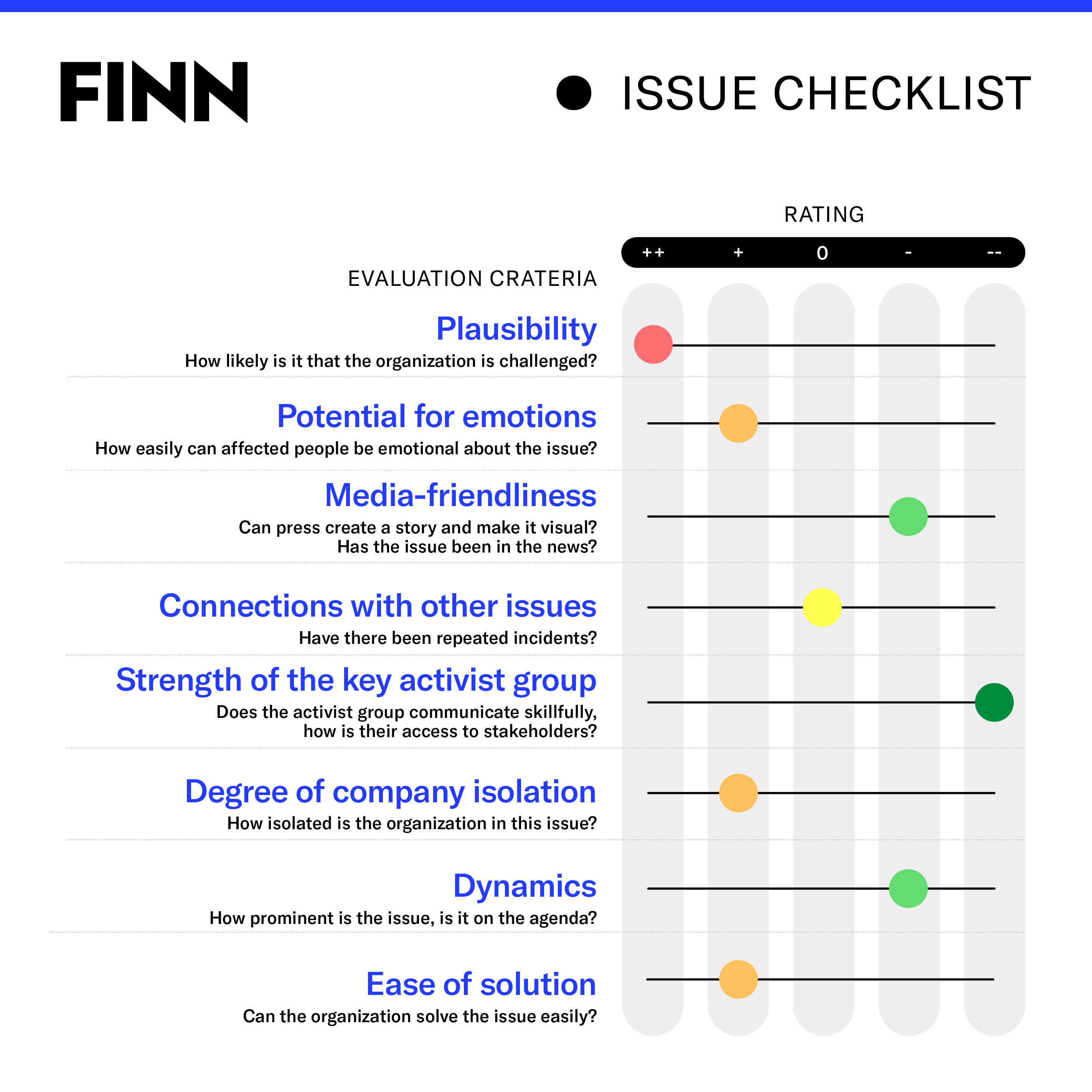

Such a tool exists – it was devised by Matthias Winter and Ulrich Steger in their book “Managing Outside Pressure“.

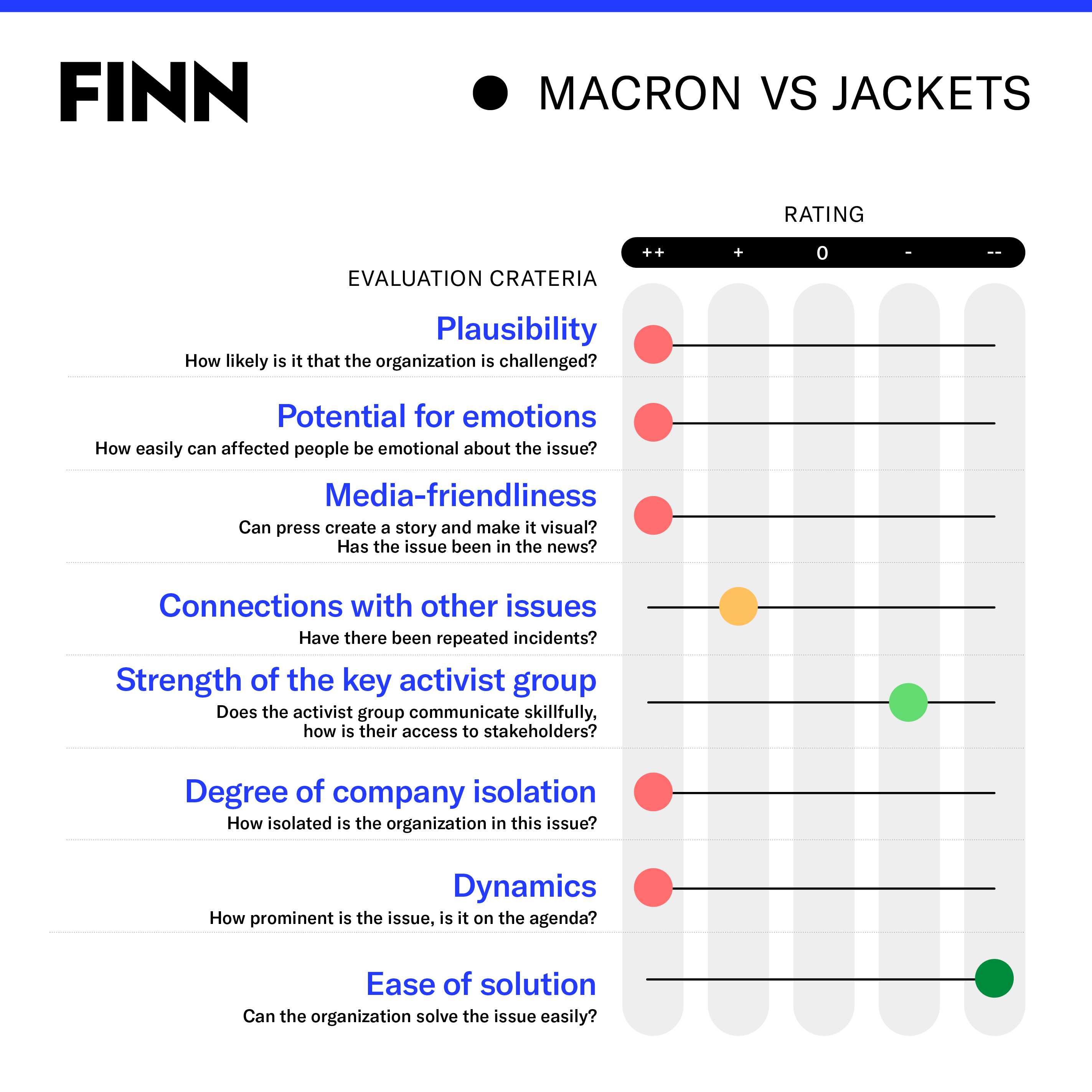

To make the tool more transparent, let us apply the checklist immediately to a case. Imagine, you are an advisor to the French president Emmauel Macron and the first ‘Yellow Jacket’ protests are just appearing on thestreets. What is your advice? Should the president respond to this or not yet? There are risks involved with both options.

However, reacting plays into the media’s love of conflicts – and could therefore make the protest larger. (“MACRON TO PROTESTERS: NO”).

Not reacting could fuel the anger of the sympathizers: “You see, I told you that Macron is a president for the rich, the ordinary French citizen means nothing to him.”

The checklist provides answers to these difficult questions. By giving a score to 8 dimensions of the issue, you can, in the end, have a better idea of the momentum of the issue.

Potential for emotions

To what extent can the issue enflame feelings? Nowadays, those feelings are often: anger or frustration.

Everything to do with identity is a sensitive matter nowadays, because that topic is so polarized. (Someone suggests renaming a Christmas Market as a Winter Market because there is no religious connotation.)

But feelings can also occur in the context of “pure” human interest stories: for example, if your issue is to do with families, children, animal suffering, care of the elderly. And then there are taboos: money and sexuality.

In Macron’s case: when it’s about purchasing power, prosperity loss and uncertainty around old age – “Will you have to be happy with less? – you can expect that emotions will run high.

Plausibility

How plausible will stakeholders feel that this issue is linked to your brand?

For example: a consumers’ association complains about Facebook’s privacy terms & conditions. (Plausible).

Another example: an action group accuses Greenpeace of unsustainable practices (Less plausible).

Please note: the question is not whetheran issue is rightly or wrongly imputed to you. It is, for example, quitepossible that some reprobate throws batteries into the general waste at Greenpeace.

The question is about: How easily can the general public be convinced that this is an issue for your organization? In the case of Macron: does the public imagine that Macron himself really has little interest in the lot of the ‘ordinary” French man?

Given his reputation as a “banker” (or even: bankster – a play on gangster) that is rather plausible.

Ready-made for media

Is the issue easy to film and photograph– or is it rather abstract? Does it concern subjects that are easily understood? Does the subject lend itself to being compared one-on-one – for example: a photograph of how a hotel sells itself online and how the hotel looks in reality?

Has the issue already been in the media? Stories that have already been reported in media are easier for journalists – if only because the story has already been tackled before – there’s already a “template” for the story.

This dimension of “media readiness” is perhaps where the genius of the ‘Yellow Jackets’ lies: several abstract, macroeconomic and slowly moving stories (taxes on diesel, energy price, purchasing power) suddenly became invigorated through a recognizable, everyday symbol: a safety vest.

Nothing is more salient for media than a group of ordinary citizens standing freezing at a petrol station.

(By now, our Macron advisor must start thinking of a response strategy.)

Links with other issues

Here, we get close to what Timothy Coombs calls “repeat incidents”.

If you get a scrape on the bodywork, stakeholders are willing to overlook that. But if your car is covered in scratches, you are a careless driver. (Oscar Wilde: “To lose one parent may be regarded ash a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.”)

Issues and crises are like magnets: they attract each other. If your organization is named within the context of one issue or crisis and a new one turns up, then you can put money on all those other instances being raked up again.

Related issues also make it more difficult to defend yourself against attacks by stakeholders. Even if you can successfully defend yourself on one of the issues, the simple accumulation of issues nevertheless means that your reputation takes a knock. “But what happened with…”, “It’s not the first time that you’ve been in the news…” are deadly expressions that you don’t want to hear when you’re managing an issue.

Here too, Macron does not score well. Despite the absence of burning issues or crises, his presidentship has already experienced a number of conflicts, and in general the protests are in line with the image of Macron as being ‘deaf’ and arrogant.

Strength of the core group among the activists

This is certainly an interesting insight from Winter and Steger. According to them, it makes no sense to try and track and score all the stakeholders involved in an in issue. Rather, Winter and Steger recommend to focus on the ‘most important activist group’ of stakeholders. This is the stakeholder who can most easily put an issue on the agenda of mainstream media. Think of it as the 80/20 rule: the most important group will drive about 80 percent of the momentum around an issue.

Powerful stakeholder groups in Belgium are NGOs, trade unions, ombudsmen and organizations such as Test-Aankoop, Bond Beter Leefmilieu or trade unions. Phenomena such as Ringland (where less organized – diffuse – stakeholders were able to set up a very powerful and sustainable movement) are exceptional. In that respect, our ‘Yellow Jackets’ have a low score.

There is no core group encouraging the activists. At least, we do not know of an interest group for the moment. On the other hand, it is highly unusual for a un- or barely organized group to mobilize people in this way.

Degree to which the organization is isolated

How isolated are you in terms of the issue? Are other companies wrestling with the same issues? In that case, it may perhaps better to leave the spokesmanship around the issue to an association or federation.

A frequently made error in issue management is ‘stepping in front of the issue’. That’s what we call it at FINN if an organization offers itself as a lightning rod for an issue, when a wiser course would have been to stay silent on the issue.

Here, you can see a distinction between issue management and crisis communication: a crisis is (almost always) aimed directly against your brand and will therefore cause direct damage to your brand. A response is then (often) appropriate.

But sometimes stakeholders and media are up in arms because of a societal theme that perhaps lies close to your day-to-day management – but that is not necessarily aimed directly against you.

Take “Occupy Wall Street”. That was aimed at “corporate greed”. Do you have to respond to that as a CEO of a large corporate? No. The action is aimed against your lifestyle, but not necessarily against your brand.

Answering the activists and “telling it like it is”, is more likely to create risk. That was something that Jamie Dimon, among others, understood well at the time: He expressed his understanding for the “Occupy” movement. In crisis communication we would call this a “minimizing strategy” (tut tut, this is not about us!). ) For Macron, it is difficult to hide: he is, for the time being, the only President of the French Republic.

How dynamic is the issue?

As we’re already said: momentum is crucial in issues and crises – the faster something is moving, the more stakeholders pay it attention.

If you see that a movement in week 1 has 100 participants in 1 location and the week after, several thousands in multiple locations, then it is not unreasonable to expect that there will be tens of thousands turning up the week after. (More about virality here)

This graph – of the famous ‘Leipzigmarches’ that brought down the DDR regime – offers an idea of what momentum and virality can do in a very short period.

The lesson here is especially that a jump from 1500 participants to 8000 (almost x5) is an acceleration that should not be underestimated.

How easy to solve?

Nothing is so annoying for the general public, and nothing is as detrimental to a company’s- or organization’s reputation as when it is perfectly capable of solving an issue, but chooses not to. If solutions are expensive and complex, stakeholders do understand that you cannot expect an organization to put things right overnight.

On the other hand, if a situation can be solved pretty quickly and the organization refuses, then the sentiment of stakeholders will be completely different – then the burden of proof lies with the organization to show that it is, nevertheless, not actually as simple as it might seem. And unfortunately stakeholders are then likely to suspect that companies are acting in bad faith rather than good faith.

Conclusion

Applied to Macron, this results in the following image:

We would argue that this a pretty bleak picture for Macron – and that he should tackle this issue accordingly.

How does your organization classify and respond to issues? Please let us know on Twitter: @finnbe or let us know in the comments!