The way a company manages the fallout of a crisis can make or break its reputation, and yet two problems persist in the way organizations of all sizes handle crises.

The first is a lack of preparation. A significant proportion of companies are ill-equipped to handle a public crisis. In a Western Union survey of Fortune 1,000 industrial companies and Fortune 500 service companies, only 54 percent of respondents reported having a crisis communication plan in place.

The second is what can best be described as “Fog of War”. When a crisis hits, typically a meeting is held with the crisis communication team to decide the course of action.

Emergency medical services often talk about the “golden hour” in which a person needs to be treated in order to save his or her life after traumatic injuries. In crisis communication however, we often see that the “golden hour” is not optimally used:

- New, often conflicting information comes in and it’s very hard to assess the quality of the information;

- Communication is not always the highest priority for some of the decision makers. They might overrule communication best practices because of irrational fears (“the media is always against us anyway”) or irrational hopes (“this will blow over if we just shut up”);

- Some of the decision makers (like operations management) might be more interested in updates coming in via mail, text and phone than in the meeting;

- Some of the important decision makers may not be on-site but travelling, requiring them to call in during the meeting or after the meeting;

- There is a lot of political capital invested in the outcome of a crisis. Some internal stakeholders might object to any and all response strategies in order to avoid blame in a worst-case outcome.

In the course of our work for clients of all sizes, we have found that principles from game theory (and its cousin, decision theory) can address these problems of crisis communication.

Game theory and crisis communication: games as a model for the real world

Game theory’s origins can be traced as far back to The Art of War, the military treatise penned by Chinese general Sun Tzu over 2,500 years ago. In the 1940s, mathematicians incorporated the principles of game theory into economic models, creating the subject as we know it today, and in the 1970s it became established in the academic world, and especially in economics as the leading instrument of studying complex problems.

A few decades ago, game theory was actually quite popular among public relations researchers.

Dr. William Ehling, a public relations professor at Syracuse University, for example, wrote in 1983 that game theory “should permit the user to make rigorous and rational distinctions in areas where conventional wisdom and ordinary thought ways have failed.”

Priscilla Murphy of Temple University was another proponent of using game theory in crisis communication:

“Nowhere is game theory more helpful than in crisis communication, where the stakes are high, decisions irrevocable and each step in the communication process yields highly visible results. Caught in a fast moving crisis, it is a natural reaction to base decisions on instinct and emotion. In contrast, game theory offers a rational structure for strategy analysis.”

Priscilla Murphy

The interest in game theory seems to have waned a bit among PR professionals, but we think that it’s useful to revisit, for two reasons: it’s excellent in a crisis preparedness setting, and it can be useful as a tactical tool when a crisis hits.

Game theory as a crisis preparedness discipline

For anyone preparing their organization for a crisis, it is useful to learn that game theorists have noticed a few patterns that appear again and again in reputational crises. Here are three of the most common scenarios that a company might have to navigate in crisis communication, as outlined in the Canadian Journal of Communication.

1. The Duel

The duel scenario is a situation in which the organization attempts to avoid fallout by temporarily remaining silent.

In these situations the company attempts to resolve the crisis before it inevitably becomes public. The longer the company waits, the more likely the press will find out. The company therefore has to balance between disclosing information prematurely and inciting a worse public reaction at a later date.

A recent example of the duel scenario is the Sony data breach. In November 2014, an enormous amount of confidential data was hacked from Sony’s computer systems and released to the public, including email exchanges, salaries, and copyrighted material.

Additionally, in the process of the breach, hackers also disabled a significant portion of Sony’s computers. Because the leak was already a matter of public knowledge, Sony had little to gain by remaining silent: the question was not if, but when, to make a statement, and what to include in the statement (which it did in the following weeks).

2. “Search and pursuit”, aka “Tag”, aka “Fox and Hounds

In a “tag” scenario, the company attempts to withhold information about the crisis indefinitely in the hopes that the scandal never get coverage.

This kind of game can be highly risky, because if the press does discover the cover-up, the company will find itself in an even worse position. Ford is one company that infamously cornered itself in this kind of dangerous game.

Case: Ford Pinto

In 1968, the Ford Pinto was developed and produced just before the proposal of new national safety regulations. For the next eight years, Ford employed numerous evasive strategies to avoid admitting that the Pinto, which had become one of the most popular cars in the United States, did indeed fail to meet the new safety requirements.

Eventually, though, the defects were confirmed to be the cause of death in multiple accidents, and Ford had to recall the cars and negotiate with federal authorities. Understandably, Ford tried to protect its short-term interests, but their efforts ultimately came at the expense of its long-term reputation:

“…organizations win little admiration in the long run from such one-sided moves. Indeed, strategists often fare worst by refusing to negotiate with the opposing player.”

3. Bargaining

In contrast to the previous scenarios, in bargaining the different stakeholders can work together to achieve an end result with which they are both satisfied.

In many PR settings, if a company communicates with the press or works in good faith with NGOs, regulators or civil society groups, both sides can gain something.

Case: Procter & Gamble

In the 1980s, Procter & Gamble was caught in a crisis when the Center for Disease Control (CDC) issued a warning about P&Gs “Rely” tampon and toxic shock syndrome. P&G initially fought the CDC to protect 20 years of R&D and marketing efforts. However, it later reversed course and started working with the CDC. It agreed to suspend sales of the tampon and to buy back unsold product. The company also volunteered its laboratory resources to research the problem and mounted an educational campaign.

Did P&G “win” something through this bargaining? Yes, it did – by bargaining with the CDC, it was allowed to save face:

“the company dropped out of the escalation game and pursued a cooperative strategy to minimize its losses. P&G worked jointly with the CDC to draft a consent agreement in which both sides conceded points to the other. The CDC allowed P&G to deny any violation of federal law or product defect.”

Priscilla Murphy (Drexel University), Source

In a game theory model, the two rounds of the game look a little bit like this:

- Round 1: Escalation by P&G. P&G escalates the conflict with the CDC to protect its business. This escalation strategy can lead to bad and catastrophic outcomes, and even in the case where P&G wins, the victory might prove Pyrrhic if the CDC retaliates.

- Round 2: Negotiation. Later, adopting a more collaborative approach with the CDC allowed the company to keep its options open, and to reduce the financial and reputational impact of the crisis.

The above examples illustrate how communication professionals can use game theory in crisis communciation exercises to make C-level familiar with some predictable patterns in crisis communication.

In our experience, senior executives are quick to grasp these concepts and enjoy the intellectual challenge of recognizing these archetypical games in different crisis communication cases and applying them to simulated crises. More importantly, familiarizing the executive team with these games offers senior execs a vocabulary and an understanding of different types of crisis response strategies that will come in handy when a real crisis hits the organization.

You can use game theoretical principles to make better decisions using accessible tools like mind maps. Here are some basic ways that game theory can help your organization respond to crises:

1. Game theory scenarios allow organizations to see through the “fog of war”

In the “fog of war” of a crisis, we often find that groups start to argue in circles, to end up with just two or three response strategies. This is because tense situations create a huge cognitive load, and people try to simplify the decision-making.

Unfortunately, that also tends to create tunnel vision. Using game theory to rationally list potential strategies, responses, and what they offer in terms of “wins” and “losses” can help diminish cognitive overload.

Case: Nestlé

In 2010, Nestlé was implicated in a viral press scandal after the company was reported to have sourced palm oil from an environmentally destructive company. When disgruntled consumers aired their grievances on Nestlé’s Facebook page, a representative responded by deleting negative comments and making rude retorts.

The social media team wanted to suppress negative publicity, but their response incited an even larger backlash that was picked up by major news outlets, including The Guardian and The Wall Street Journal. Ultimately, the company failed to consider the full range of consequences to their actions. A more careful consideration of the possible countermoves of the opponents might have made the team realize that:

- Sustainability is an important topic in the media (and in corporate annual reports)

- NGOs enjoy excellent access to media

- Corporations trying to suppress negative reputational information fit a story archetype

- Conventional crisis communication wisdom tells us that ‘the cover-up is worse than the crime’

In short, mapping scenarios in a more detailed way, it would have been clear to anyone that “censoring” Facebook comments might create a backlash. Conventional media wisdom also tells us that “the cover-up is worse than the crime”. By quickly going over the schematic to see what there is “to win” and “to lose” for every response strategy, it would have been clear that the backlash scenario was far worse than a “do nothing” or “make a statement” scenario.

In the end, Nestlé not only suffered reputational damage, but also financial losses from reduced sales and stock prices as well—a large price to pay for a dilemma that is rather straightforward if you take the time to map it out.

While this seems a straightforward exercise, this type of mistake is still quite common.

Using a simple model like the one we presented in the visual can show why some responses might be tempting if you only focus on the upside, but that every scenario has a downside too.

In crises, it’s exceedingly rare to find a silver bullet that will solve all the organization’s problems. More likely, the organization needs to be guided through careful weighing up of the potential upside of different responses as well as the potential negative outcomes.

2.Game theory can show that apparently attractive scenarios are highly risky

Part of what makes a crisis so difficult to handle is that the company in question may not know all the facts.

It can be difficult to plan for negative outcomes when the outcomes themselves are a matter of uncertainty, or when the motivations of the “opposing” player are not fully known. But in public relations crises, the key stakeholders are often media, and they typically follow a predictable logic: they want to find facts and break news.

The same goes for regulators and parliamentary hearing commissions, NGOs and consumer interest groups.

Most of your “opponents” will be highly motivated to bring out information, because they know that reputational damage on your side will make it more likely that you will adopt an accommodating position, as Timothy Coombs calls it in his Situational Crisis Communication Theory. In other words, making you look bad is the best way to get concessions from you.

In a crisis, therefore, it’s always healthy to assume that there is at least a chance that information that you thought was safe or hidden will get out. It also makes sketching scenarios a little easier. Often, your worst-case scenario will be the one where all the information about the crisis and the organization’s response to it becomes public.

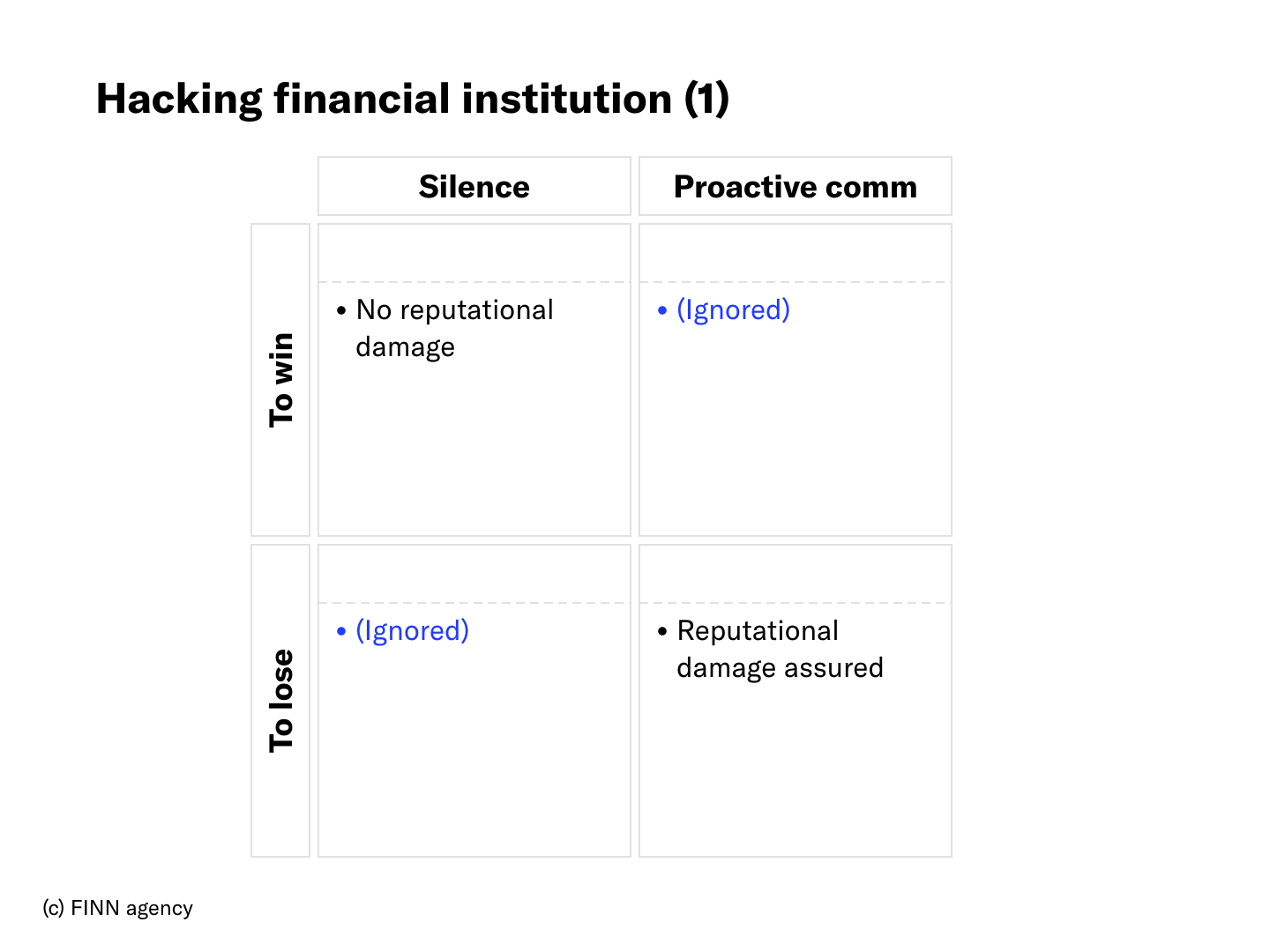

Case: a financial institution is hacked

Facts: a financial institution, which was one of our clients, was hacked, which led to financial loss for some of their B2B customers. The losses were significant for the customers involved, but limited to a handful of victims. The victims were notified of the breach, as was a trade federation representing those customers to warn them about the problem.

Our advice was to proactively notify all customers by newsletter and press release, to explain the circumstances of the hack and to explain how to protect against it.

Our arguments were that phishing and hacking attempts occur daily, and it’s inevitable that some will slip past the defenses of consumers and financial institutions. We argued that the media would not be surprised by the fact that hacking exists, that it sometimes succeeds, and would be relatively underwhelmed by the amounts and number of victims.

The client, however, considered the customers to be at fault for the hack (which had occurred on the computer of the customers rather than the systems of the financial institution), and considered the case to be contained: all parties had been notified, and they had upped the security of their systems to avoid further breaches. They updated their website with general advice on “how to keep your account safe”.

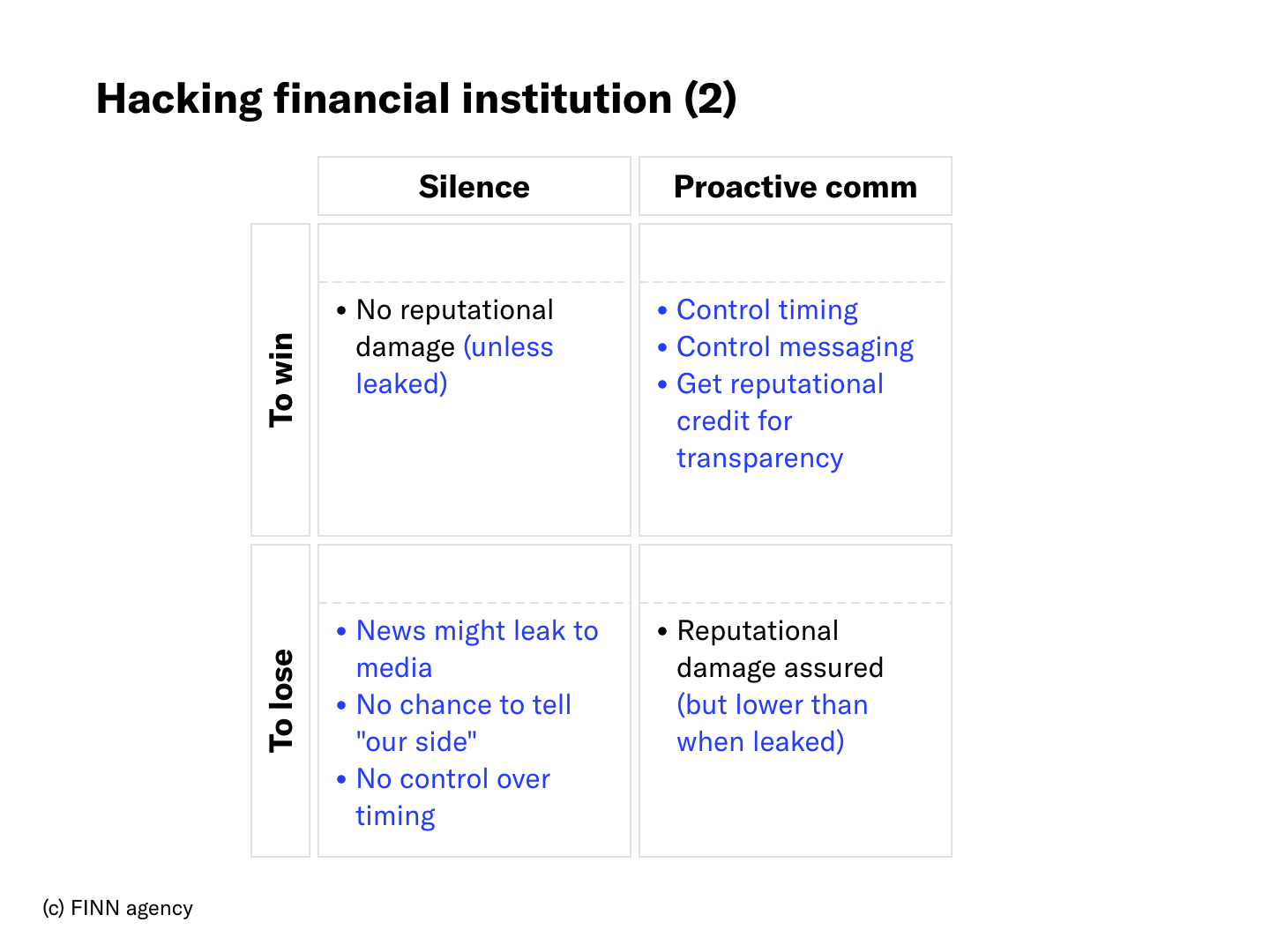

They regarded proactive communication as ‘too risky’ because it would invite all sorts of scrutiny. In short, their mental model looked like this:

Two weeks later, the breach was front page news in a prominent newspaper. The customers vehemently disagreed with the notion that they had been responsible for the hack, and had taken the initiative to notify the press, accusing the client of lax security and of not wanting to take (financial) responsibility for what had happened. Going to the press was clearly a move to put pressure on the client to obtain reimbursement for the victims.

The problem here was twofold: first, our client saw only two scenarios – one that would lead to a ‘win’ and one that would lead to a ‘loss’. Secondly, the client underestimated the fact that the stakeholders had a motivation to put the screws on the organization by leaking the news of the breach. Reputational damage would make it harder for the client to deny the victims compensation.

The most difficult task for communication advisers in these situations is to convince management that if some stakeholders know of the breach, then it will inevitably percolate through to the media. And if the news leaked, then all the ‘bad’ outcomes would materialize – but with a worse impact than if the company had communicated proactively. The real model looked like this, with Scenario 1.2 being a mirror of Scenario 2 (but with extra damage):

If there is a high chance of a leak, then intuitively you can feel that this is a bad strategy. This has been proven in theory and practice time and time again. Mapping the decision tree like you would in game theory helps the executives weigh the outcomes better.

Key insights & conclusion

1. Game theory can help C-level understand how stakeholders behave in a crisis

Classifying crises and crisis responses can go a long way towards explaining reputational crises to executive teams. By taking them through a few examples and showing the outcomes, C-level might gain a better understanding of the dynamics of a crisis.

Our experiences have shown that C-level grasp these concepts quite easily and often enjoy the intellectual challenge of thinking through different scenarios and trade-offs. By introducing these types of crisis “games” in crisis preparedness settings, executive teams acquire a vocabulary that can be used to manage crises when they occur.

2. Game theoretical concepts can help map realistic scenarios

Organizations tend to associate certain scenarios with “wins” and others with “losses”, whereas in reality, every scenario will require trade-offs. Also, every crisis response choice can have repercussions on the next ‘round’ of the crisis – either because of an opponent reacts to it (media, NGO, regulator,…) or because new information becomes available that sheds another light on the crisis response.

A step-by-step process that lists things “to win” as well as things “to lose” for every response strategy, and that thinks through the next round of events or countermoves from stakeholders, might help avoid that mistake.

3. Game theory concepts can show “dominated strategies”

A core concept of game theory is the ‘dominated strategy’. This is a strategy that will result in an equally bad or worse outcome, in any scenario. In many cases, hoping for the crisis to blow over can be regarded as a dominated strategy, and yet we see that organizations favor it. A good scenario can show that a certain strategy is dominated and help the organization avoid a bad crisis response.

4. Using a strong process allows organizations to take charge

The worst thing that can happen in a crisis is when the crisis communication team is stalled because it cannot agree on a response strategy, or because there are long discussions over payoffs. Using a strong process to create a shared decision tree allows the team to make visible progress and work together towards the least damaging response strategy.